Standing Where They Stood: What MLK Day Means to Green Mountain Justice

A reflection on pilgrimage, proximity, and the unfinished work of beloved community

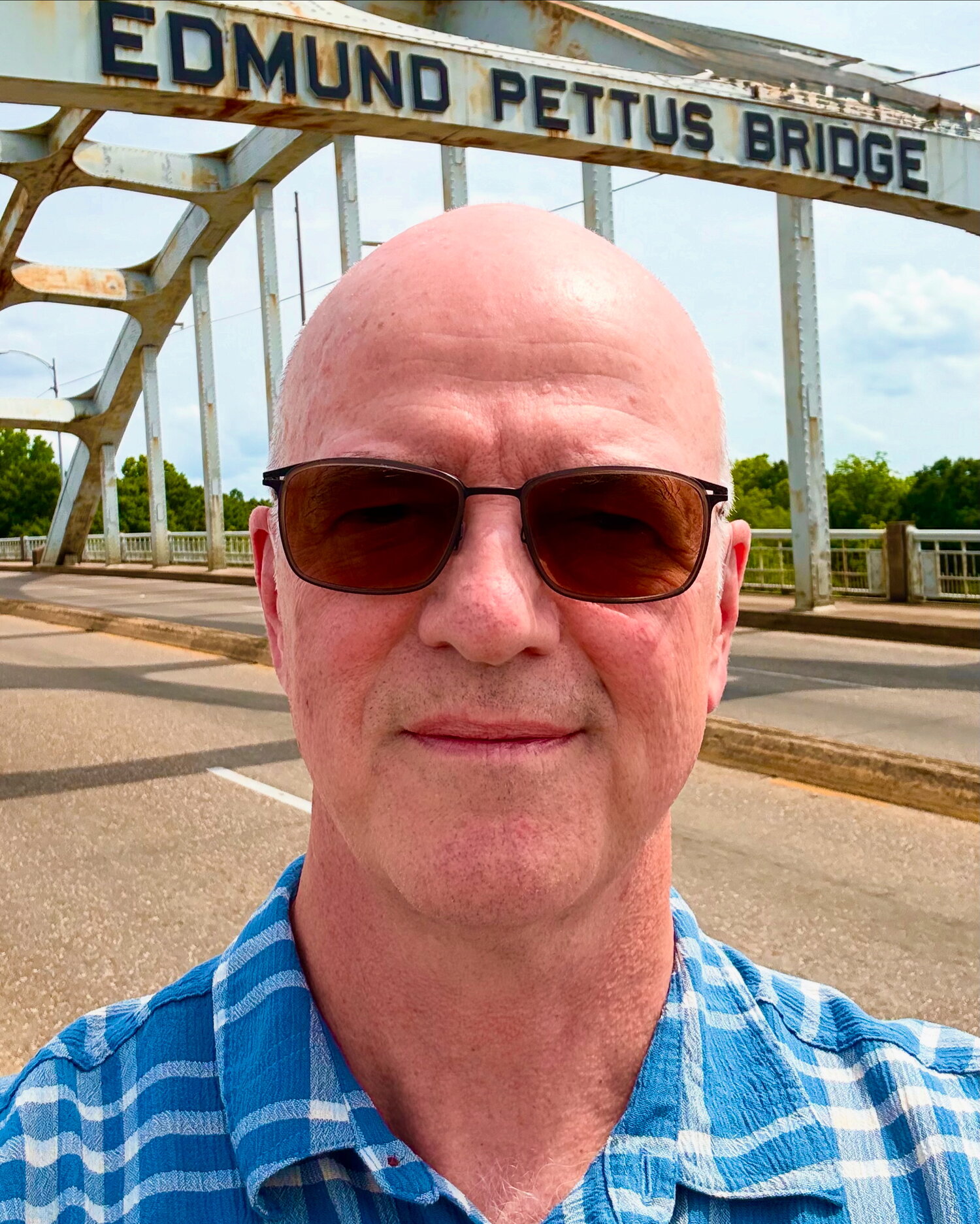

Last May, I walked across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma. I stood in the sanctuary of Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta. I sat in the study of Dr. King’s Montgomery parsonage, where he wrote sermons that bent the arc of history.

These weren’t tourist stops. They were sacred ground.

But what gutted me most wasn’t a museum or monument. It was a living room on Dynamite Hill.

Barbara Shores and the Bombed House

In Birmingham, our seminary group received an extraordinary invitation. Barbara Shores, daughter of Arthur Shores—Dr. King’s attorney—welcomed us into her home.

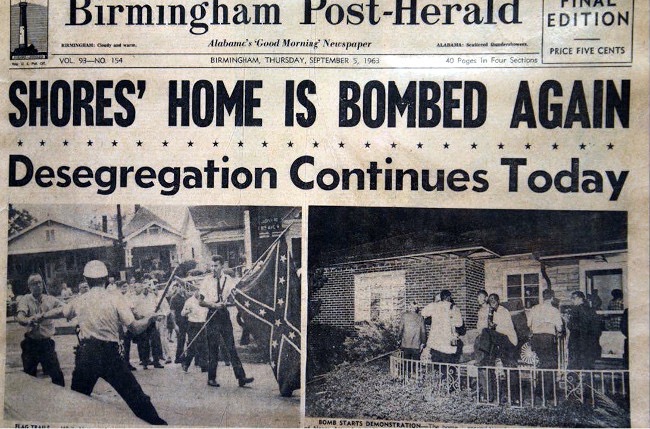

Her home had been bombed. Multiple times. The living room we sat in had been rebuilt three times. Enemies of justice targeted this house so often that the neighborhood earned its name: Dynamite Hill. Yet here she lives. Still.

Think about that. Not moved away. Not retreated to safety. Still here. In the same house. On the same street. Doing the same work her father did.

For some people, social justice is a cause. An issue. A sermon topic. A hashtag. Something you post about, vote on, maybe donate to. For Barbara Shores, justice isn’t something she does. It’s the life she was born into. The life she stayed in. The price her family paid in shattered windows and rebuilt walls. Three times.

I sat on the same bar stool at the same bar, which was unremarkable, except that it is where her father and Dr. King would sit, planning the legal strategies that would dismantle Jim Crow. Barbara made us iced tea. We spent hours in that living room listening to her stories. The books stacked on her coffee table told their own history—works on Obama, civil rights, justice, and liberation. The art on the walls. The framed photographs. Every corner of that house held memory and meaning.

This is what proximal ministry actually costs. Not discomfort. Not inconvenience. Risk. Persistence. Showing up in the same place, day after day, year after year, even when they keep trying to blow it up.

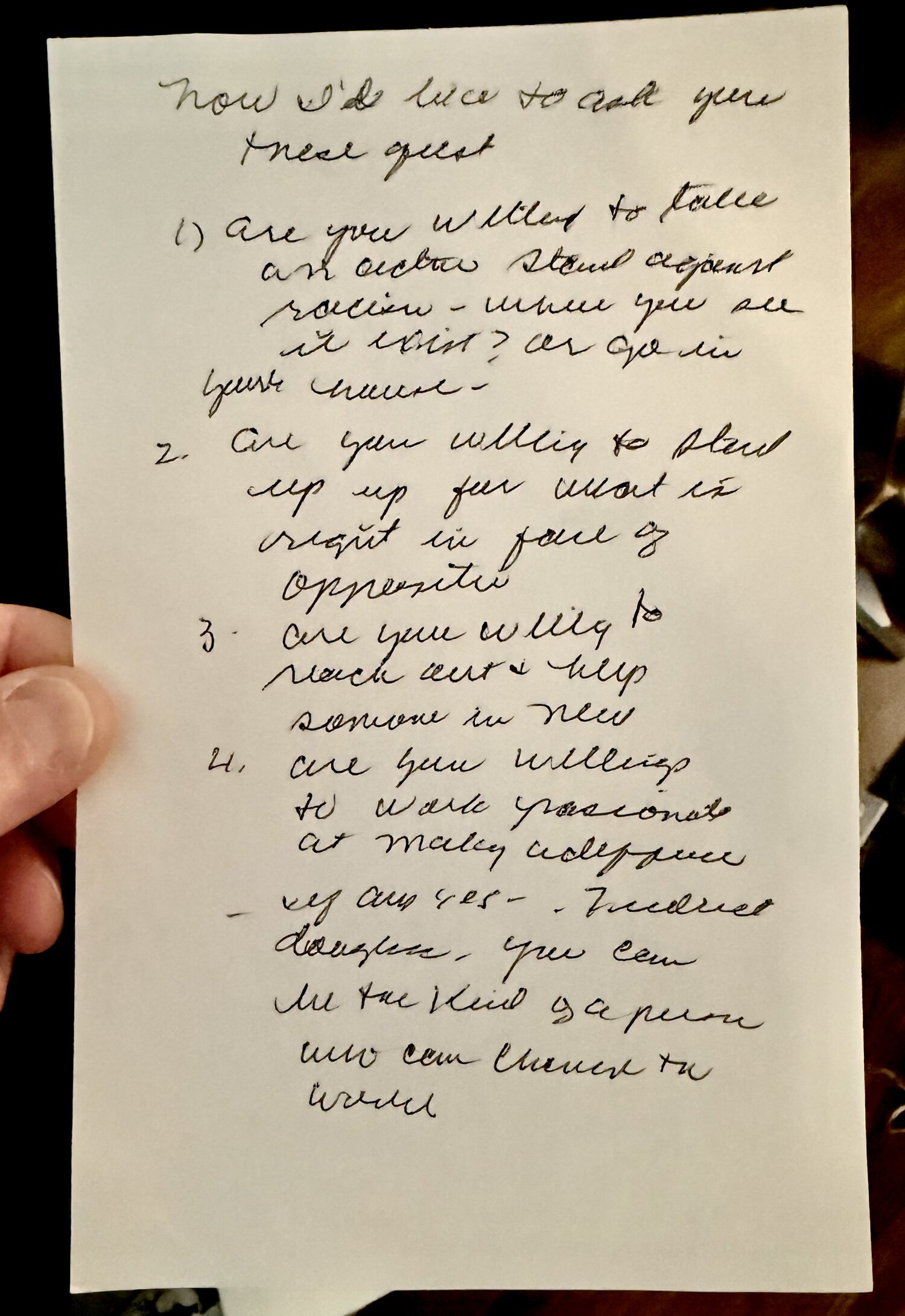

When our time ended, Barbara didn’t give us a speech. She asked us questions.

Questions For a Life (not Just a Lifestyle) of Justice

As we prepared to leave, Barbara Shores read four questions from her handwritten a piece of paper:

- Are you willing to take an active stand against racism wherever you see it exist?

- Are you willing to stand up for what is right in the face of opposition?

- Are you willing to reach out and help someone in need?

- Are you willing to work passionately at making a difference?

Then she looked at us and said: “If you answered yes to these questions, you are the kind of person who can change the world.”

Boy howdy, did that land.

Not as inspiration. As obligation. As calling.

What Proximity Teaches

The study tour through Birmingham, Selma, Montgomery, and Atlanta wasn’t an academic exercise. It was immersion in the embodied reality of what justice and injustice actually cost.

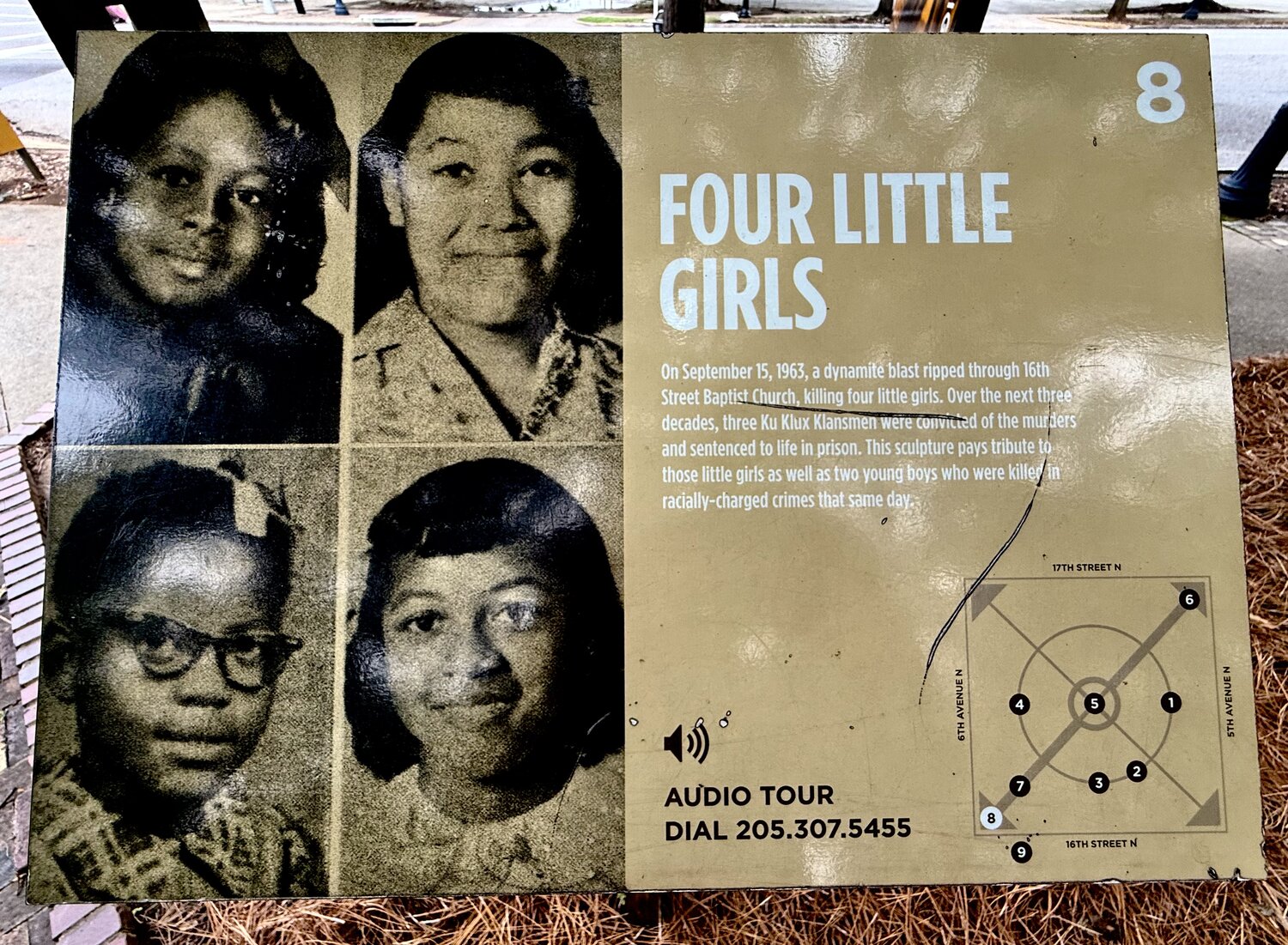

At 16th Street Baptist Church, I stood where Addie Mae Collins, Carol Denise McNair, Carole Rosamond Robertson, and Cynthia Diane Wesley were murdered on September 15, 1963. Four girls. A Sunday morning.

At the Equal Justice Initiative’s Legacy Museum, I picked up a prison phone and listened to an incarcerated person tell me their story—then thank me for listening. The world should hear these voices.

At the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, I walked among 800 steel monuments, each representing a county where racial terror lynchings occurred. Jars of soil from lynching sites. Names inscribed. History made undeniably physical.

These places closed the distance of history for me. They made justice not an abstraction but an empirical reality. They transformed theological questions from comfortable theory to urgent practice.

From Alabama to Vermont

So what does any of this have to do with Green Mountain Justice? Everything.

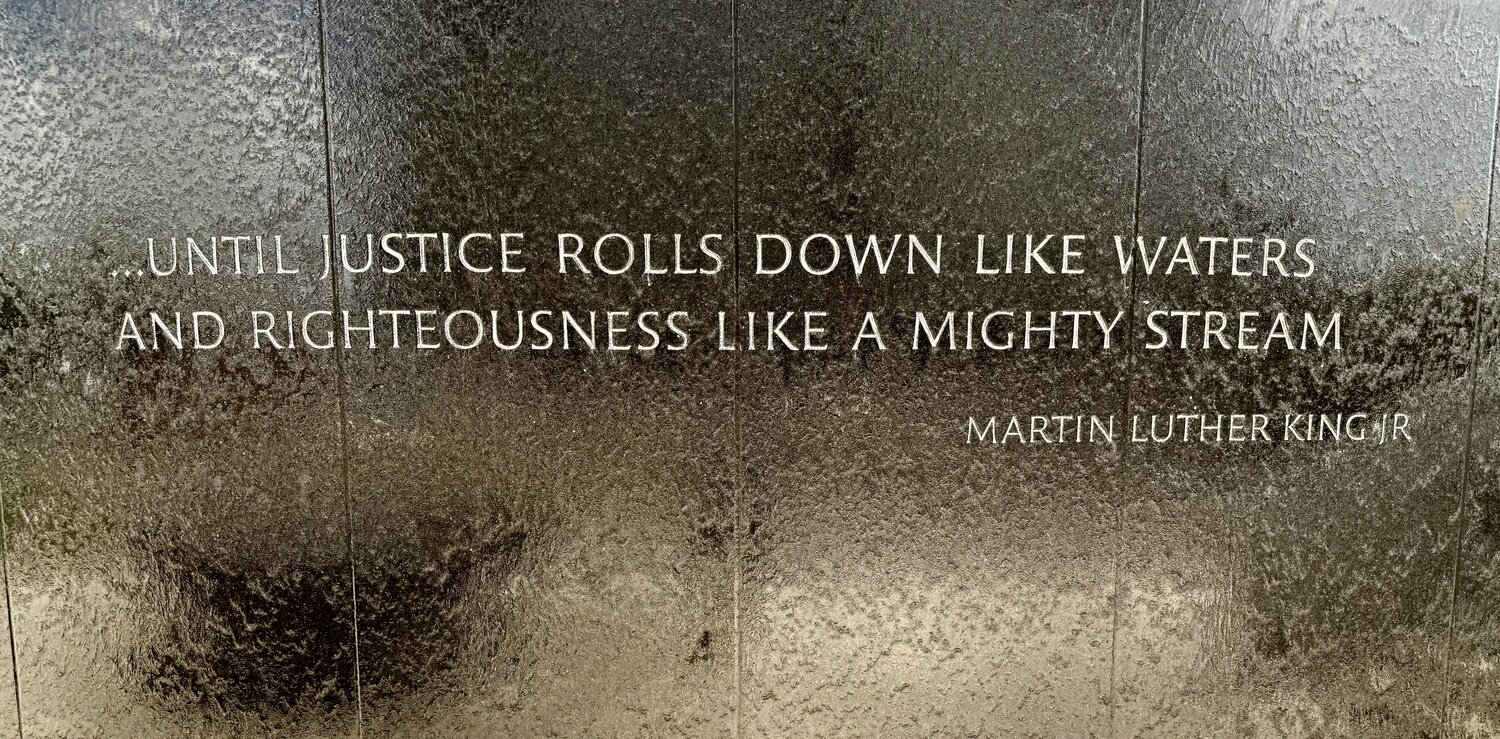

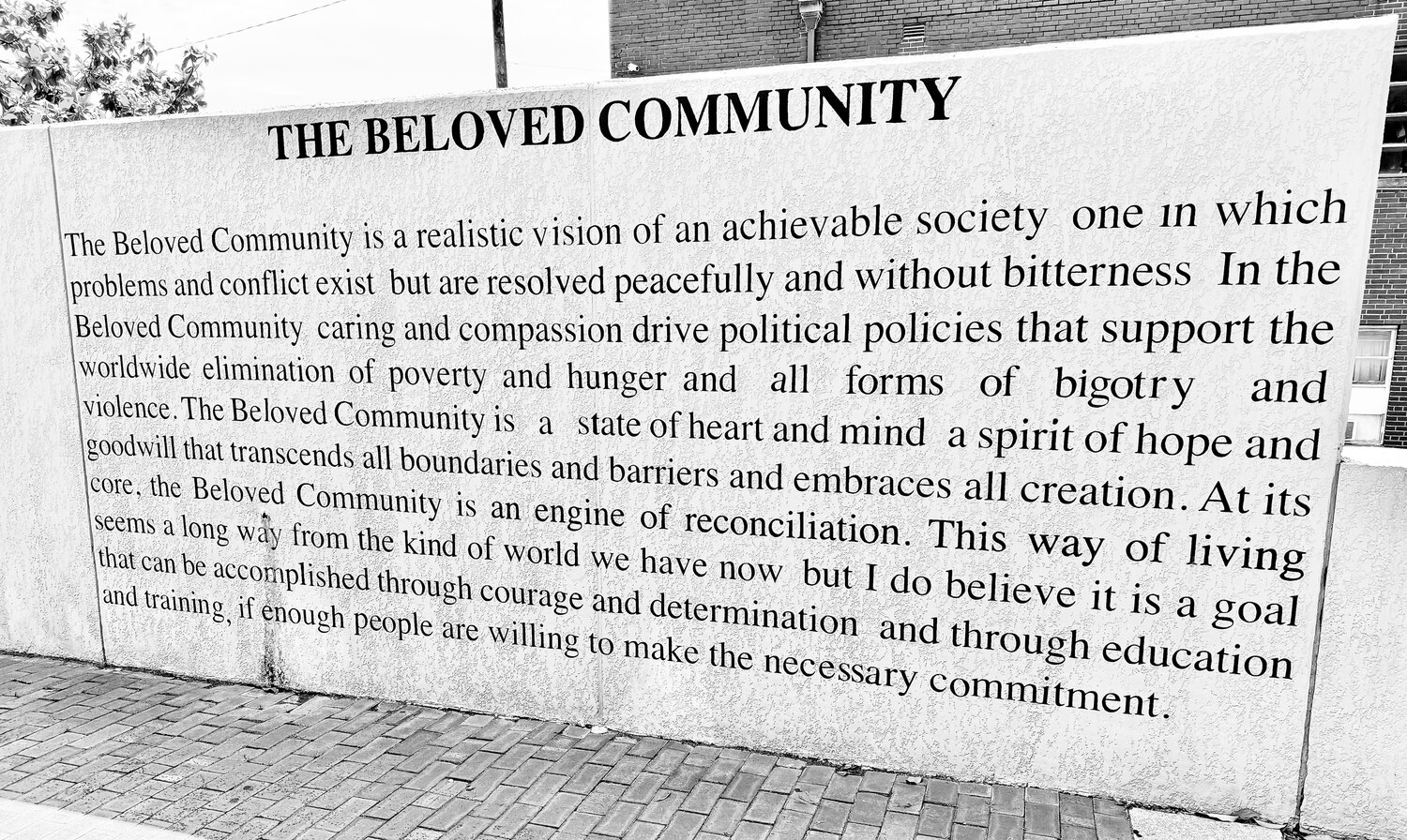

Dr. King’s vision of the Beloved Community wasn’t a metaphor. It was a blueprint. As the monument at the King Center states:

“The Beloved Community is a realistic vision of an achievable society, one in which problems and conflict exist but are resolved peacefully and without bitterness.”

At GMJ, we believe beloved community cannot be built through transactions—not through forms, not through looking at computer screens instead of into eyes, not through the comfortable distance that separates “helpers” from “helped.”

Ministry isn’t something we do for people. It’s something we do with them.

That’s what Barbara Shores modeled. She didn’t lecture us. She invited us in. She made us tea. She asked us questions. She trusted us with her story and her sacred space.

That’s proximity. That’s relationship. That’s how transformation happens.

The Unfinished Work

The marchers who crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge in 1965 petitioned the governor with what they called “the only peaceful and nonviolent resources at our command: our physical presence and the moral power of our souls.”

Sixty years later, the work remains unfinished. In Vermont. In America. Everywhere.

Our neighbors living at the margins still face systems designed to exclude them. Unhoused families still seek shelter in bitter cold. People with lived experience of injustice still find their voices silenced by those with the privilege of distance.

At Green Mountain Justice, we try to answer Barbara Shores’ questions every day. Not with speeches or strategic plans. With presence. With relationship. With the stubborn belief that beloved community gets built person by person, moment by moment. And tomorrow, no matter what, we’ll show up again.

The Call

This MLK Day, I’m not just remembering history. I’m recommitting to the work that makes history—the slow, unglamorous, relational work of showing up.

Are you willing to take an active stand?

Are you willing to stand up in the face of opposition?

Are you willing to reach out and help someone in need?

Are you willing to work passionately at making a difference?

If your answer is yes, then you are the kind of person who can change the world.

Tom Morgan is the founder of Green Mountain Justice (greenmountainjustice.org), a Vermont community justice ministry building beloved community through proximity, relationship, and the centering of marginalized neighbors.

The photos in this post were taken during a May 2025 Chicago Theological Seminary study tour “Justice at the Intersections.”

Your donations to Green Mountain Justice are 100% tax-deductible. Green Mountain Justice, Inc. is a registered 501(c)(3) Vermont nonprofit, EIN 39-4582526.